Finally a little bit of spare time to do some blog writing. I have discussed the issues of monitoring training loads in my previous posts #1,#2,#3.

Also, I have written a previous post on strength and power assessment and vertical jumping tests.

So, I am not going to discuss testing techniques here, but rather discuss what monitoring is all about and how to use it and offer some solutions/ideas.

Monitoring is definitively a sexy topic as everyone seems to be “monitoring” something in training. To the extent that some athletes are also now flooded with questionnaires, spreadsheets, forms to fill in. Most of such information I have to say it is totally useless as it does not get used and/or is totally irrelevant for designing better training programmes.

Why testing and monitoring training then? First principles first:

Testing and monitoring are useful tools only if they allow you to analyse the athlete’s level and be able to define and adapt a training programme.

If you are measuring something that does not help you in modifying the training plan you are wasting your time!

Also, you should make sure you measure things using methods that are valid and reliable! For more information about validity and reliability I suggest you read Will Hopkins’ excellent blog here. If you use measurement tools and modalities that are not valid and reliable you are wasting your time!

Testing and monitoring are tools to help you in making better decisions with your training planning. They are not standalone activities and you should question everyone of them in terms of cost effectiveness not only in financial terms but also in terms of athletes’ time. I have seen in too many sports athletes filling too many questionnaires and forms that are neither valid nor reliable nor provide any meaningful info to the coaching staff.

Planning training is just like business. Testing and monitoring will tell you where you are now. Strategic planning, analysis of specific performance trends (or world trends) and goal setting will help you in defining where you need/want to be. The how you get there is your training plan. If testing does not help you in getting a better HOW, it is just a useless data collection exercise.

Most of all, a proper approach to testing and monitoring can make sure you avoid insanity and learn what works and what does not work with you athletes.

So, what should be the approach?

In my view it is relatively simple. You need to be able to collate all the information you decided to collect, analyse it, make some sense of it and build a “dashboard” to visualise what is going on in order to be able to intervene where necessary. One of the approaches I suggested previously involves the use of radar charts to profile each individual athlete in comparisons to team scores. Similar approaches can be used even with individual athletes just comparing the magnitude of changes in their own scores:

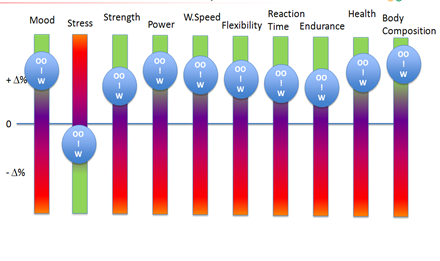

However, a more comprehensive view could be obtained using what I call a “performance equaliser”. The example below shows how some specific scores ca be plotted with an equaliser dashboard and visually show how specific parameters can change during a training season.

Performance Equaliser #1: Beginning of training phase

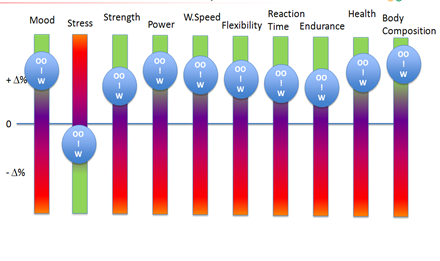

Performance Equaliser #2: After few weeks

This approach can be used to evaluate each athlete’s situation and take appropriate action as well as providing an easy to understand reporting structure. I have used green and red to express good change and not so good change.

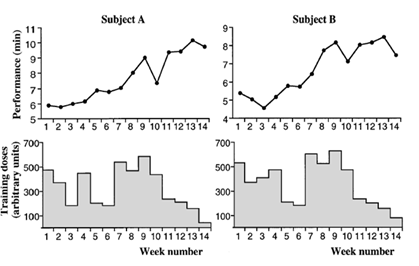

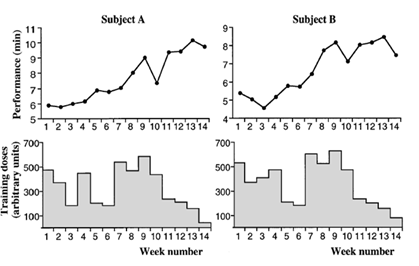

Good, continuous data can also help in having a more complex data analysis approach involving the possibility of data modelling and simulation to be able to predict some outcomes. The example below from Busso et al. (2007, JAP) is just an example of the scientific literature on modelling.

This is one of the areas I am working on as I have a keen interest in computational statistical models applied to training and performance data and I have to say that there is very limited information on this topic and the few experiments also have very limited samples sizes (I found a couple of paper with n=1!). A review of the literature is now planned and I hope it will be ready for 2011 thanks to the hard work of an excellent PhD student working on this topic in my lab.

Many companies are now offering all sorts of software to analyse data using typical modelling approaches such us decision trees, Monte Carlo methods, etc. However it is important to state that the quality of the analysis is as good as the data you collect. So, again, you get what you put in it. Also, if your data are wrong, you will definitively make the wrong calls!

Despite the fact that simulations and data modelling have a certain degree of error (from very very large to relatively small), I still believe that this is something to pursue as I believe that nowadays some good continuous basic data can be collected and they can provide some useful information. As Richard Dawkins stated in his book “The Selfish Gene” “[…] of course there are good models of the World an bad ones, and even the good ones are only approximations. No amount of simulation can predict exactly what will happen in reality, but a good simulation is enormously preferable to blind trial and error!” R. Dawkins (2006).

Another useful approach can be the use of simple mathematical/financial laws as the Law of Diminishing Returns. The law of diminishing returns states that as the quantities of an input increase, the resulting rate of output increase eventually decreases.

This is exactly what we see in training. We increase and decrease training volume and intensity and we see changes in performance (output) which increase or decrease if we do too much work.

Recent work from my colleague Dr. Brent Alvar’s lab have shown how such approach can be used to analyse for example the effectiveness of strength training following a meta-analytical approach (for more info, click on the graph below).

Despite the fact that others criticised this approach for analysing the effectiveness of multiple vs. single sets using literature data, I believe that such approach can and should be used to understand the effectiveness of a training programme (or the return for your investment in time and effort). This should help in understanding the dose-response relationship to training loads in your athletes.

I am sure I have not covered a lot of aspects, and I am sure I will change my mind about a few of the things I wrote in the future (this is what learning is all about!). But at the moment I feel that monitoring training is a very useful thing to do and some statistical approaches can be applied to extract useful information to translate analysis into actions.

So, to summarise, here is some advice:

- Are your tests valid and reliable?

- What is the error of measurement? (What is the noise of your data?)

- What are you measuring?

- Are you able to use the data you gather to action changes to the programme?

- What is the investment in time/costs/effort to collect the data? Is it worthwhile?

_ How long does it take to receive the data in order to analyse them? (e.g. blood tests tend to be analysed few days after you collected them)

- Can you collect some valid, reliable, non subjective data with high frequency?

- Are the data good enough and frequent enough to allow you to make some predictions?

orcid.org/0000-0002-2777-8707

orcid.org/0000-0002-2777-8707